Shingles and chickenpox (Varicella-zoster virus)

Highlights

Chickenpox Vaccine Recommendations

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends the following chickenpox (varicella) vaccination schedules for:

- Children ages 12 months - 12 years. All healthy children should receive their first chickenpox shot at age 12 - 15 months and a second shot at age 4 - 6 years (preferably before entering pre-kindergarten, kindergarten, or first grade).

- Adolescents and Adults ages 13 years and older. All healthy teenagers and adults who have never had chickenpox or the vaccine should receive 2 doses of the varicella vaccine, given 4 - 8 weeks apart.

Shingles Vaccine Recommendations

The shingles (herpes zoster) vaccine (Zostavax) is now approved for adults age 50 years and older with healthy immune systems. It was originally approved in 2006 for adults age 60 years and older. In March 2011, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) lowered the recommended age for the vaccine. However, the CDC has not yet added the shingles vaccine to its list of recommended vaccines for adults ages 50 - 59, and most insurance companies will not pay for the shot for adults younger than age 60. There is no maximum age for getting the vaccine.

Home Remedies for Chickenpox Relief

Chickenpox is uncomfortable and unpleasant, but most cases are relatively mild and resolve within 7 - 10 days. In otherwise healthy people who have a low risk for complications, home remedies can help provide relief from itching and fever.

- Oatmeal baths can help relieve itching.

- Calamine lotion can help dry out blisters and soothe skin.

- Acetaminophen (Tylenol, generic) can help reduce fever.

- Antihistamines may relieve severe itching and aid sleep.

Most important, don’t scratch! Scratching the blisters can cause scarring and lead to a secondary infection.

Introduction

Shingles and chickenpox are both caused by a single virus of the herpes family, known as varicella-zoster virus (VZV). The word herpes is derived from the Greek word "herpein," which means "to creep," a reference to a characteristic pattern of skin eruptions. VZV causes two different clinical illnesses:

- Varicella, or chickenpox, develops after an individual is exposed to VZV for the first time.

- Herpes zoster, or shingles, develops from reactivation of the virus later in life, usually many decades after chickenpox.

Varicella (Chickenpox)

Most people get chickenpox from exposure to other people with chickenpox. It is most often spread through sneezing, coughing, and breathing. It is so contagious that few nonimmunized people escape this common disease when they are exposed to someone else with the disease.

When people with chickenpox cough or sneeze, they expel tiny droplets that carry the varicella virus. If a person who has never had chickenpox or never been vaccinated inhales these particles, the virus enters the lungs. From here it passes into the bloodstream. When it is carried to the skin it produces the typical rash of chickenpox.

People can also catch chickenpox from direct contact with a shingles rash if they have not been immunized by vaccination or by a previous bout of chickenpox. In such cases, transmission happens during the active phase when blisters have erupted but not formed dry crusts. A person with shingles cannot transmit the virus by breathing or coughing.

Herpes Zoster (Shingles)

During a bout of chickenpox, the varicella-zoster virus travels to nerve cells called dorsal root ganglia. These are bundles of nerves that transmit sensory information from the skin to the brain. Here, the virus can hide from the immune system and remain inactive but alive for years, often for a lifetime. This period of inactivity is called latency.

If the virus becomes active after being latent, it causes the disorder known as shingles, or herpes zoster. The virus spreads in the ganglion and to the nerves connecting to it. Nerves most often affected are those in the face or the trunk. The virus can also spread to the spinal cord and into the bloodstream.

Shingles itself can develop only from a reactivation of the varicella-zoster virus in a person who has previously had chickenpox. In other words, shingles itself is never transmitted from one person to another either in the air or through direct exposure to the blisters.

It is not clear why the varicella-zoster virus reactivates in some people but not in others. In many cases, the immune system has become impaired or suppressed from certain conditions such as AIDS, other immunodeficiency diseases, or certain cancers or drugs that suppress the immune system. Aging itself increases the risk for shingles.

Other Herpes Viruses

The varicella-zoster virus belongs to a group of herpes viruses that includes eight human viruses (it also includes animal viruses). Herpes viruses are similar in shape and size and reproduce within the structure of a cell. The particular cell depends upon the specific virus. Human herpes viruses include herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1), which usually causes cold sores, and herpes simplex virus 2 (HSV-2), which usually causes genital herpes. Cytomegalovirus (CMV), which causes mononucleosis-like illness and retinitis, and Epstein-Barr Virus (EBV), the cause of classic mononucleosis, are also human herpes viruses.

All herpes viruses share some common properties, including a pattern of active symptoms followed by latent inactive periods that can last for months, years, or even a lifetime.

Risk Factors

Risk Factors for Chickenpox (Varicella)

Between 75 - 90% of chickenpox cases occur in children under 10 years of age. Before the introduction of the chickenpox (varicella) vaccine, about 4 million cases of chickenpox were reported in the U.S. each year. Since a varicella vaccine became available in the U.S. in 1995, the incidence of disease and hospitalizations due to chickenpox has declined by nearly 90%.

Chickenpox usually occurs in late winter and early spring months. It can also be transmitted from direct contact with the open blisters associated with either chickenpox or shingles. (Clothing, bedding, and other such objects do not usually spread the disease.)

A patient with chickenpox can transmit the disease from about 2 days before the appearance of the spots until the end of the blister stage. This period lasts about 5 - 7 days. Once dry scabs form, the disease is unlikely to spread.

Most schools allow children with chickenpox back 10 days after onset. Some require children to stay home until the skin has completely cleared, although this is not necessary to prevent transmission.

Recurrence of Chickenpox. Recurrence of chickenpox is possible, but uncommon. One episode of chickenpox usually means lifelong immunity against a second attack. However, people who have had mild infections may be at greater risk for a breakthrough, and more severe, infection later on particularly if the outbreak occurs in adulthood.

Risk Factors for Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

Shingles affects about one out of every three adults. About 1 million cases of shingles occur each year in the U.S. Anyone who has had chickenpox has risk for shingles later in life. Certain factors increase the risk for such outbreaks.

The Aging Process. The risk for herpes zoster increases as people age. The risk for postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is also highest in older people and increases dramatically after age 50. PHN is persistent nerve pain and is the most feared complication of shingles.

Immunosuppression. People whose immune systems are damaged from diseases such as AIDS or childhood cancer have a risk for herpes zoster that is much higher than those with healthy immune systems. Herpes zoster in people who are HIV-positive may be a sign of full-blown AIDS. Certain drugs used for treating HIV, such as protease inhibitors, may also increase the risk for herpes zoster.

Cancer. Cancer places people at risk for herpes zoster. At highest risk for developing shingles are those with Hodgkin's disease followed by patients with lymphomas. Chemotherapy itself increases the risk for herpes zoster.

Immunosuppressant Drugs. Patients who take certain drugs that suppress the immune system are at risk for shingles (as well as other infections). They include:

- Azathioprine (Imuran)

- Chlorambucil (Leukeran)

- Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan)

- Cyclosporine (Sandimmune, Neoral)

- Cladribine (Leustatin)

- Infliximab (Remicade)

- Adalimumab (Humira)

- Prednisone and other corticosteroids

These drugs are used for patients who have undergone organ transplantation and are also used for treating autoimmune diseases. Such disorders include rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, diabetes, multiple sclerosis, Crohn's disease, and ulcerative colitis.

Risk Factors for Shingles in Children. Although most common in adults, shingles occasionally develops in children. Children with immune deficiencies are at highest risk. Children with no immune problems who had chickenpox before they were 1 year old also have a higher risk for shingles.

Risk for Recurrence of Shingles. Shingles can recur, but the risk is low (about 6%). Evidence suggests that a first zoster episode may boost the immune system to ward off another attack. However, people who had long-lasting shingles pain after their first episode, or patients who are immunocompromised, may be at higher risk for recurrence.

Complications

Chickenpox (varicella) rarely causes complications, but it is not always harmless. It can cause hospitalization and, in rare cases, death. Fortunately, since the introduction of the vaccine in 1995, hospitalizations have declined by nearly 90%, and there have been few fatal cases of chickenpox. The major long-term complication of varicella is the later reactivation of the herpes zoster virus and the development of shingles. Shingles occurs in about 20% of people who have had chickenpox.

Older adults have the greatest risk for dying from chickenpox, with infants having the next highest risk. Males (both boys and men) have a higher risk for a severe case of chickenpox than females. Children who catch chickenpox from family members are more likely to have a severe case than if they caught it outside the home. The older the child, the higher the risk for a more severe case. But even in such circumstances, chickenpox is rarely serious in children.

Other factors put individuals at specifically higher risk for complications of the varicella-zoster virus. Patients with diseases, such as Hodgkin's disease, who receive bone marrow or stem cell transplants are at higher risk for herpes zoster and its complications.

Although a pregnant woman has a very low risk for contracting chickenpox, if she does become infected the virus increases her risk for life-threatening pneumonia. Infection in the pregnant woman in the first trimester also poses a 1 - 2% chance for infecting the developing fetus and potentially causing birth defects. Herpes zoster is extremely rare in pregnant women, and there is almost no risk for the unborn child in such cases.

Specific Complications of Chickenpox (Varicella)

Aside from itching, the complications described below are very rare.

Itching. Itching, the most common complication of the varicella infection, can be very distressing, particularly for small children. Many home remedies can help relieve the discomfort. [See: "Treatment for Chickenpox" section below.]

Secondary Skin Infections and Scarring. Small scars may remain after the scabs have fallen off, but they usually clear up within a few months. In some cases, a secondary infection may develop at sites that the patient scratched. The infection is usually caused by the bacteria Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus pyogenes. Permanent scarring may occur as a result. Children with chickenpox are at much higher risk for this complication than adults are, probably because they are more likely to scratch.

Bacterial superinfection of the skin caused by group A streptococcus is the most common serious complication of chickenpox (but it is still rare). The infection is usually mild, but if it spreads in deep muscle, fat, or in the blood, it can be life threatening. Infection can cause serious conditions, such as necrotizing fasciitis (the so-called flesh-eating bacteria) and toxic shock syndrome (TSS). Symptoms include:

- A persistent or recurrent high fever

- Redness, pain, and swelling in the skin and the tissue beneath

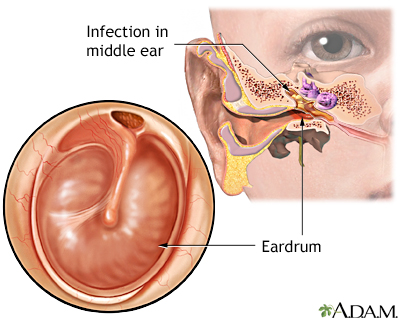

Ear Infections. Some children experience ear infections from chickenpox. Hearing loss is a very rare result of this complication.

Pneumonia. Pneumonia is suspected if coughing and abnormally rapid breathing develop in patients who have chickenpox. Adults and adolescents with chickenpox are at some risk for serious pneumonia. Pregnant women, smokers, and those with serious medical conditions are at higher risk for pneumonia if they have chickenpox. Oxygen and intravenous acyclovir are key treatments for this condition. Pneumonia that is caused by varicella can result in lung scarring, which may impair oxygen exchange over the following weeks, or even months.

Neurological Complications.

- Inflammation in the Brain. Encephalitis and meningitis, infection or inflammation in the central nervous systems, can occur in rare cases in both children and adults. This condition can be very dangerous, causing coma and even death.

- Stroke. Although stroke in children is extremely rare, a condition called cerebral vasculitis, in which blood vessels in the brain become inflamed, has been associated with varicella-zoster. Varicella may be a factor in some cases of stroke in young adults.

Reye Syndrome. Reye syndrome, a disorder that causes sudden and dangerous liver and brain damage, is a side effect of aspirin therapy in children who have chickenpox or influenza. The disease can lead to coma and is life threatening. Symptoms include rash, vomiting, and confusion beginning about a week after the onset of the disease. Because of the strong warnings against children taking aspirin, this condition is, fortunately, very rare. Children should never take aspirin when they have a viral infection or fever. Acetaminophen (Tylenol, generic) is the preferred drug for fever or pain in patients younger than age 18 years.

Disseminated Varicella. Disseminated varicella, which develops when the virus spreads to organs in the body, is extremely serious and is a major problem for patients with compromised immune systems.

Specific Complications of Shingles (Herpes Zoster)

Postherpetic Neuralgia. Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is pain that persists for longer than a month after the onset of herpes zoster. It is the most common severe complication of shingles. Risk factors for PHN include:

- Age. PHN affects about 25% of herpes zoster patients over 60 years old. The older a person is, the longer PHN is likely to last. It rarely occurs in people under age 50.

- Gender. Some studies suggest that women may be at slightly higher risk for PHN than men.

- Severe or complicated shingles. People who had prodromal symptoms or a severe attack (numerous blisters and severe pain) during the initial shingles episode are also at high risk for PHN. The rate is also higher in people whose eyes have been affected by zoster.

In most cases, PHN resolves within 3 months. Studies report that only about 10% of patients experience pain after a year. Unfortunately, when PHN is severe and treatments have not been very effective, the persistent pain and abnormal sensations can be profoundly frustrating for patients.

Skin Infections. If the blistered area is not kept clean and free from irritation, it may become infected with group A Streptococcus or Staphylococcus bacteria. If the infection is severe, scarring can occur.

In very rare cases, herpes zoster has been associated with Stevens-Johnson syndrome, an extensive and serious condition in which widespread blisters cover mucous membranes and large areas of the body.

Eye Infections. If shingles occurs in the face, the eyes are at risk, particularly if the path of the infection follows the side of the nose. If the eyes become involved (herpes zoster ophthalmicus), a severe infection can occur that is difficult to treat and can threaten vision. Patients with HIV/AIDS may be at particular risk for a chronic infection in the cornea of the eye.

Herpes zoster can also cause a severe infection in the retina called imminent acute retinal necrosis syndrome. In such cases, visual loss develops within weeks or months after the herpes zoster outbreak has resolved. Although this complication usually follows a herpes outbreak in the face, it can occur after an outbreak in any part of the body.

Neurological Complications.

- Guillain-Barre Syndrome. Guillain-Barre syndrome is caused by inflammation of the nerves and has been associated with a number of viruses, including herpes zoster. The arms and legs become weak, painful, and, sometimes, even paralyzed. The trunk and face may be affected. Symptoms vary from mild to severe enough to require hospitalization. The disorder resolves in a few weeks to months. Other herpes viruses (cytomegalovirus and Epstein-Barr), or bacteria (Campylobacter) may have a stronger association with this syndrome than herpes zoster.

- Ramsay Hunt Syndrome. Ramsay Hunt syndrome occurs when herpes zoster causes facial paralysis and rash on the ear (herpes zoster oticus) or in the mouth. Symptoms include severe ear pain and hearing loss, ringing in the ear, loss of taste, nausea, vomiting, and dizziness. Ramsay Hunt syndrome may also cause a mild inflammation in the brain. The dizziness may last for a few days, or even weeks, but usually resolves. Severity of hearing loss varies from partial to total; however, this too usually goes away. Facial paralysis, on the other hand, may be permanent.

- Bell's Palsy. Bell's palsy is partial paralysis of the face. Sometimes, it is difficult to distinguish between Bell's palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome, particularly in the early stages. In general, Ramsay Hunt syndrome tends to be more severe than Bell's palsy.

- Meningitis and Encephalitis. Inflammation of the membrane around the brain (meningitis) or in the brain itself (encephalitis) is a rare complication in people with herpes zoster. The encephalitis is generally mild and resolves in a short period. In rare cases, particularly in patients with impaired immune systems, it can be severe and even life threatening.

- Stroke. Some research suggests that herpes zoster increases the risk for stroke in the year following a shingles outbreak.

Disseminated Herpes Zoster. As with disseminated chickenpox, disseminated herpes zoster, which spreads to other organs, can be serious to life-threatening, particularly if it affects the lungs. People with compromised immune systems are at greatest danger. It is very rare in people with healthy immune systems.

Symptoms

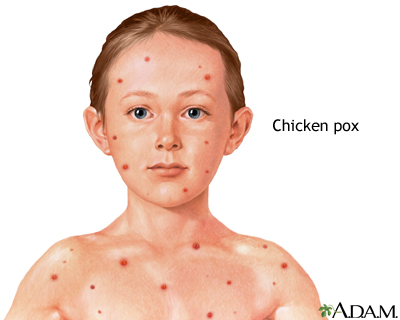

Symptoms of Chickenpox

The time between exposure to the virus and eruption of symptoms is called the incubation period. For chickenpox, this period is 10 - 20 days. The patient often develops fever, headache, swollen glands, and other flu-like symptoms before the typical rash appears. While fevers are low grade in most children, some can reach 105 °F.

These symptoms subside once the rash breaks out. One or more tiny raised red bumps appear first, most often on the face, chest, or abdomen. They become larger within a few hours and spread quickly (sprout), eventually forming small blisters on a red base. The numbers of blisters vary widely. Some patients have only a few spots, others can develop hundreds. Each blister is filled with clear fluid that becomes cloudy in several days.

It takes about 4 days for each blister to dry out and form a scab. During its course, the rash itches, sometimes severely. Usually separate crops of blisters occur over 4 - 7 days, the entire disease process lasting 7 - 10 days.

Symptoms of Shingles

Shingles nearly always occurs in adults. Usually two, and sometimes three, identifiable symptom stages occur:

Prodrome. In the prodrome phase, a cluster of warning symptoms appear 3 - 4 days before the outbreak of the infection. These symptoms range from general feelings of malaise (chills, fever, nausea, and muscle aches) to abnormal sensations such as tingling, itching, burning, or a feeling of “pins and needles” accompanied by deep pain. The skin may be unbearably sensitive to touch.

Active Infection. After prodrome, a rash appears, usually on the trunk. However, the rash can develop in other areas as well, such as legs, arms, face, or neck. The rash is typically confined to one side of the body and follows the same track of inflamed nerves as the prodrome pain.

- The rash usually starts as well-defined, small, red clear spots.

- Within 12 - 24 hours, these pimples develop into small fluid-filled blisters. The blisters grow, merge, and become pus-filled, and are extremely painful.

- Within about 7 - 10 days (as with chickenpox), the blisters form crusts and heal. In some cases it may take as long as a month before the skin clears completely.

Sometimes pain develops without a rash, a condition known as zoster sine herpete.

Postherpetic Neuralgia. Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is pain that persists for longer than a month after the onset of herpes zoster. Typical symptoms include:

- Pain that is described as deep aching, burning, stabbing, or like an electric shock

- Extreme sensitivity to touch or temperature changes

- The pain is persistent, but may come and go.

Diagnosis

Both chickenpox (varicella) and shingles (zoster) can usually be diagnosed by symptoms alone. If a diagnosis is still unclear after a physical examination, laboratory diagnostic tests may be required. These tests use samples of fluid taken from the blister. They are generally used to distinguish between varicella-zoster and herpes simplex viruses.

Ruling out Other Disorders

Ruling out Disorders that Resemble Chickenpox. Chickenpox, particularly in early stages, may be confused with herpes simplex, impetigo, insect bites, or scabies.

Ruling out Disorders that Resemble Shingles. The early prodrome stage of shingles can cause severe pain on one side of the lower back, chest, or abdomen before the rash appears. It therefore may be mistaken for other disorders, such as gallstones, that cause acute pain in internal organs.

In the active rash stage, shingles may be confused with herpes simplex, particularly in young adults, if the blisters occur on the buttocks or around the mouth. Herpes simplex, however, does not usually generate chronic pain.

A diagnosis may be difficult if herpes zoster takes a non-typical course in the face, such as with Bell's palsy or Ramsay Hunt syndrome, or if it affects the eye or causes fever and delirium.

Vaccination

There are two types of varicella vaccines:

- A chickenpox vaccine for vaccinating children, adolescents, and adults

- A shingles vaccine for vaccinating adults age 50 years and older

Chickenpox vaccine

The live-virus varicella vaccine (Varivax) produces persistent immunity against chickenpox. The vaccine can prevent chickenpox or reduce the severity of the illness if it is used within 3 days, and possibly up to 5 days, after exposure to the infection.

The childhood chickenpox vaccine can also be given as part of a combination vaccine (Proquad) that combines measles, mumps, rubella (together called MMR), and varicella in one product. However, the CDC advises that combining varicella and MMR vaccinations into one shot doubles the risk for febrile (fever-related) seizures in children ages 12 - 24 months compared to giving separate MMR and varicella injections. Even with the combination vaccine the risk is low, but parents should consider the lower risk associated with separate injections.

The combination varicella and MMR vaccine is usually recommended for the second dose, in children ages 4 - 6 years, as it is not associated with increased risk for febrile seizures in this age group. However, children who are at higher risk for seizures due to a personal or family medical history should generally receive the MMR and varicella vaccines separately.

Recommendations for the Chickenpox Vaccine in Children

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommends that children receive TWO doses of the chickenpox vaccine with:

- The first dose administered when the child is 12 - 15 months years of age

- The second dose administered when the child is 4 - 6 years of age

For children who have previously received one dose of the chickenpox vaccine, the ACIP recommends that they receive a “catch-up” second dose during their regular doctor’s visit. This second dose can be given at any time as long as it is at least 3 months after the first dose. Doctors pushed for the new second-dose policy due to a number of recent chickenpox outbreaks among previously vaccinated schoolchildren. Studies indicate that the odds of developing chickenpox are 95 lower in children who receive two doses of the vaccine compared to those who receive only one.

Children most at risk for having chickenpox after having been vaccinated only one time are ages 8 - 12 years and have generally been vaccinated at least 5 years before their current chickenpox infection.

Recommendations for the Chickenpox Vaccine in Adults

The CDC recommends that every healthy adult without a known history of chickenpox be vaccinated. Adults should receive 2 doses of the vaccine, 4 - 8 weeks apart. Adults in the following groups should especially consider vaccination:

- Those with high risk of exposure or transmission (hospital or day care workers, parents of young children)

- People who may come in contact with those who have compromised immune systems

- Nonpregnant women of childbearing age

- International travelers

As with other live-virus vaccines, the chickenpox vaccine is not recommended for:

- Women who are pregnant or who may become pregnant within 30 days of vaccination. (Women who are pregnant and not immunized should receive the first dose of the vaccine upon completion of their pregnancy.)

- People whose immune systems are compromised by disease or drugs (such as after organ transplantation).

Patients who cannot be vaccinated but who are exposed to chickenpox receive immune globulin antibodies against varicella virus. This helps prevent complications of the disease if they become infected.

Side Effects. Most side effects are mild and include pain at the injection site and low-grade fever. In rare cases, the vaccine may produce a mild rash within about a month of the vaccination, which can transmit chickenpox to others. Individuals who have recently been vaccinated should avoid close contact with anyone who might be susceptible to severe complications from chickenpox until the risk for a rash passes.

Shingles Vaccine

The herpes zoster (shingles) vaccine (Zostavax) is a stronger version of the chickenpox vaccine. It was originally approved in 2006 for adults age 60 years and older. In 2011, the FDA lowered the recommended age for Zostavax to 50. Because the vaccine contains live virus, it cannot be administered to people with weakened immune systems. However, the CDC has not yet added the shingles vaccine to its list of recommended vaccines for adults ages 50 - 59, and most insurance companies will not pay for the shot for adults younger than age 60. There is no maximum age for getting the vaccine.

A single shot of the vaccine can reduce the risk of developing shingles by 55 - 70 percent and may also help prevent postherpetic neuralgia and ophthalmic herpes. However, although the shingles vaccine is strongly recommended for older adults with healthy immune systems, many patients are not receiving it. Barriers to vaccination may include limited insurance coverage and the sometimes limited availability of the vaccine product.

Varicella-Zoster Immune Globulin

Varicella-zoster immune globulin (VariZIG) is a substance that mimics the normal immune response against the varicella-zoster virus. It is used to protect high-risk patients who are exposed to chickenpox. Such groups include:

- Pregnant women with no history of chickenpox who have not been previously immunized

- Newborn infants whose mothers had signs or symptoms of chickenpox around the time of delivery (5 days before to 2 days after)

- Premature infants

- Immunocompromised children and adults with no antibodies to VZV

- Recipients of bone-marrow transplants (even if they have had chickenpox)

- Patients with a debilitating disease (even if they have had chickenpox)

For these patients, VariZIG should be given within 96 hours of exposure to someone with chickenpox. (Note: VariZIG is a new formulation of an older drug called VZIG, which is no longer produced.)

Treatment for Chickenpox

Home Treatments for Chickenpox

Acetaminophen. Patients with chickenpox do not have to stay in bed unless fever and flu symptoms are severe. To relieve discomfort, a child can take acetaminophen (Tylenol, generic), with doses determined by the doctor. A child should never be given aspirin, or medications containing aspirin, as aspirin increases the risk for a dangerous condition called Reye syndrome.

Soothing Baths. Frequent baths are particularly helpful in relieving itching, when used with preparations of finely ground (colloidal) oatmeal. Commercial preparations (Aveeno) are available in drugstores, or one can be made at home by grinding or blending dry oatmeal into a fine powder. Use about 2 cups per bath. The oatmeal will not dissolve, and the water will have a scum. Adding baking soda (1/2 - 1 cup) to a bath may also help.

Lotions. Patients can apply calamine lotion and similar over-the-counter preparations to the blisters to help dry them out and soothe the skin.

Antihistamines. For severe itching, diphenhydramine (Benadryl, generic) is useful and may help children sleep.

Preventing Scratching. Small children may have to wear mittens so that they don't scratch the blisters and cause a secondary infection. All patients with varicella, including adults, should have their nails trimmed short.

Acyclovir for Chickenpox

Acyclovir is an antiviral drug that may be used in adult varicella patients or those of any age with a high risk for complications and severe forms of chickenpox. The drug may also benefit smokers with chickenpox, who are at higher than normal risk for pneumonia. Some doctors recommend its use for children who catch chickenpox from other family members because such patients are at risk for more serious cases. To be effective, oral acyclovir must be taken within 24 hours of the onset of the rash. Early intravenous administration of acyclovir is an essential treatment for chickenpox pneumonia.

Treatment for Shingles

The treatment goals for an acute attack of herpes zoster include:

- Reduce pain

- Reduce discomfort

- Hasten healing of blisters

- Prevent the disease from spreading

Over-the-counter (OTC) remedies are often effective in reducing the pain of an attack. Antiviral drugs (acyclovir and others), oral corticosteroids, or both are sometimes given to patients with severe symptoms, particularly if they are older and at risk for postherpetic neuralgia (PHN).

Home Treatments for Shingles

Applied Cold. Cold compresses soaked in Burrow's solution (an over-the-counter powder that is dissolved in water) and cool baths may help relieve the blisters. It is important not to break blisters as this can cause infection. Doctors advise against warm treatments, which can intensify itching. Patients should wear loose clothing and use clean loose gauze coverings over the affected areas.

Itch Relief. In general, to prevent or reduce itching, home treatments are similar to those used for chickenpox. Patients can try antihistamines (particularly Benadryl), oatmeal baths, and calamine lotion.

Over-the-Counter Pain Relievers. For an acute shingles attack, patients may take over-the-counter pain relievers:

- Children should take acetaminophen. (Shingles is very rare in children.)

- Adults may take aspirin or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as ibuprofen (Advil, other brands, generic). These remedies, however, are not very effective for postherpetic neuralgia.

Antiviral Drugs

Antiviral drugs do not cure shingles, but they can reduce the severity of the attack, hasten healing, and reduce the duration. They may also reduce the risk of postherpetic neuralgia.

Antiviral drugs approved for treatment of shingles include:

- Acyclovir (Zovirax, generic) is the oldest, most studied of these drugs

- Famciclovir (Famvir, generic) and valacyclovir (Valtrex, generic) are now preferred to treat herpes zoster in most patients because they require fewer daily doses than acyclovir.

These anti-viral drugs are usually taken for 7 days. To be effective, they should be started within 72 hours of the onset of infection. The earlier they are given the more effective these drugs are. Side effects may include stomach cramps, nausea, diarrhea, headache, and dizziness. Acyclovir may have more side effects than the other two drugs. People who have kidney problems or weakened immune systems may need to take a lower dose of these medications.

Foscarnet (Foscavir) is an injectable antiviral drug that can be used to treat cases of varicella-zoster infection resistant to acyclovir and similar drugs. It is rarely necessary.

Treatment for Postherpetic Neuralgia

Postherpetic neuralgia (PHN) is difficult to treat. Once PHN develops, a patient may need a multidisciplinary approach that involves a pain specialist, primary care physician, and other health care providers.

The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) treatment guidelines for postherpetic neuralgia recommend:

- Tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline, nortriptyline, desipramine, maprotiline)

- Anticonvulsants (gabapentin and pregabalin)

- Lidocaine skin patches

- Opioids (oxycodone, methadone, morphine)

Topical Treatments for Postherpetic Neuralgia

Creams, patches, or gels containing various substances can provide some pain relief.

- Lidocaine. A patch that contains the anesthetic lidocaine (Lidoderm, generic) is approved specifically for postherpetic neuralgia (PHN). One to four patches can be applied over the course of 24 hours. Another patch (EMLA) contains both lidocaine and prilocaine, a second anesthetic. The most common side effects are skin redness or rash.

- Capsaicin. Capsaicin is a chemical compound found (in hot chili peppers. A prescription capsaicin skin patch (Qutenza) is approved for pain relief of PHN. The patch must be applied by a health care professional, as placement of the patch can be painful. Because the patch may increase blood pressure, the patient should be monitored for at least 1 hour after the patch is applied. A lower-concentration ointment form of capsaicin (Zostrix) is available over the counter, but its benefits may be limited.

- Topical Aspirin. Topical aspirin, known chemically as triethanolamine salicylate (Aspercreme, generic), may bring relief.

- Menthol-Containing Preparations. Topical gels containing menthol, such as high-strength Flexall 454, may be helpful.

Tricyclic Antidepressants

Tricyclic antidepressants may help relieve PHN pain. Nortriptyline (Pamelor, generic), amitriptyline (Elavil, generic), and desipramine (Norpramin, generic) are the standard drugs used for treating PHN.

It may take several weeks for the drugs to become fully effective. They do not work as well in patients who have burning pain or allodynia (pain that occurs with normally non-painful stimulus, such as a light touch or wind).

Unfortunately, tricyclics have side effects that are particularly severe in the elderly, who are also more likely to have PHN. Desipramine and nortriptyline have fewer side effects than amitriptyline and are preferred for older patients. Side effects include dry mouth, blurred vision, constipation, dizziness, difficulty urinating, disturbances in heart rhythms, and an abrupt drop in blood pressure when standing up.

Anticonvulsant (Anti-Seizure) Drugs

Certain anticonvulsant drugs have effects that may be helpful for PHN. (Anticonvulsant drugs are also known as anti-seizure drugs.) Gabapentin (Neurontin, generic) and pregabalin (Lyrica) are approved for treatment of PHN. Side effects may include dizziness, sleepiness, blurry vision, weight gain, trouble concentrating, and swelling of hands and feet. Anticonvulsant medications can increase the risk of suicidal thoughts and behavior.

Opioids and Opioid-like Drugs

Opioids. Patients with severe pain that does not respond to tricyclic antidepressants or anticonvulsants may need powerful painkilling opioid drugs. The use of narcotics is controversial as these drugs can be addictive. These drugs may be taken by mouth or delivered through a skin patch. Oxycodone is the standard opioid for PHN. It is available in different formulations (Percocet, Percodan, Oxycontin, ro generic.) Morphine may also used. Constipation, drowsiness, and dry mouth are common side effects of opioids.

Tramadol. Tramadol (Ultram, generic) is a pain reliever that is used as an alternative to opioids. It has opioid-like properties but is not as addictive. (Dependence and abuse have been reported, however.) Side effects are similar to opoids.

Pain Management Techniques

A number of relaxation and stress-reduction techniques may be helpful for managing chronic pain. They include meditation, deep breathing exercises, biofeedback, self-hypnosis, and muscle relaxation. Psychotherapy approaches such as cognitive behavioral therapy may help patients learn how to cope with and manage their responses to pain.

Surgery

Certain surgical techniques in the brain or spinal cord attempt to block nerve centers associated with postherpetic neuralgia. These methods carry risk for permanent damage, however, and should be used only as a last resort when all other methods have failed and the pain is intolerable. Most studies indicate that surgery does not relieve PHN pain.

Resources

- www.cdc.gov -- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- www.niaid.nih.gov -- National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases

- www.ninds.nih.gov -- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke

- www.aan.com -- American Academy of Neurology

References

Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. Recommended adult immunization schedule: United States, 2011. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Feb 1;154(3):168-73.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases. Prevention of varicella: recommendations for use of varicella vaccines in children, including a recommendation for a routine 2-dose varicella immunization schedule. Pediatrics. 2007 Jul;120(1):221-31.

Chen N, Li Q, Zhang Y, Zhou M, Zhou D, He L. Vaccination for preventing postherpetic neuralgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Mar 16;3:CD007795.

Committee on Infectious Diseases; American Academy of Pediatrics. Policy statement--recommended childhood and adolescent immunization schedules -- United States, 2011. Pediatrics. 2011 Feb;127(2):387-8.

Harpaz R, Ortega-Sanchez IR, Seward JF; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention of herpes zoster: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008 Jun 6;57(RR-5):1-30.

Kang JH, Ho JD, Chen YH, Lin HC. Increased risk of stroke after a herpes zoster attack: a population-based follow-up study. Stroke. 2009 Nov;40(11):3443-8. Epub 2009 Oct 8.

Kimberlin DW, and Whitley RJ. Varicella-zoster vaccine for the prevention of herpes zoster. N Engl J Med. 2007 Mar 29;356(13):1338-43.

LaRussa PS, Marin M. Varicella-zoster virus infections. In: Kliegman RM, Stanton BF, St. Geme III JW, et al, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 19th ed. Saunders; 2011:chap 245.

Lu PJ, Euler GL, Harpaz R. Herpes zoster vaccination among adults aged 60 years and older, in the U.S., 2008. Am J Prev Med. 2011 Feb;40(2):e1-6.

Marin M, Broder KR, Temte JL, Snider DE, Seward JF; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Use of combination measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella vaccine: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010 May 7;59(RR-3):1-12.

Marin M, Güris D, Chaves SS, Schmid S, Seward JF; Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention of varicella: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007 Jun 22;56(RR-4):1-40.

Marin M, Meissner HC, Seward JF. Varicella prevention in the United States: a review of successes and challenges. Pediatrics. 2008 Sep;122(3):e744-51.

Sampathkumar P, Drage LA, Martin DP. Herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009 Mar;84(3):274-80.

Schmader KE, Levin MJ, Gnann JW Jr, McNeil SA, Vesikari T, Betts RF, et al. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of herpes zoster vaccine in persons aged 50-59 years. Clin Infect Dis. 2012 Apr;54(7):922-8. Epub 2012 Jan 30.

Shapiro ED, Vazquez M, Esposito D, Holabird N, Steinberg SP, Dziura J, et al. Effectiveness of 2 doses of varicella vaccine in children. J Infect Dis. 2011 Feb 1;203(3):312-5.

Tseng HF, Smith N, Harpaz R, Bialek SR, Sy LS, Jacobsen SJ. Herpes zoster vaccine in older adults and the risk of subsequent herpes zoster disease. JAMA. 2011 Jan 12;305(2):160-6.

Tyring SK. Management of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007 Dec;57(6 Suppl):S136-42.

Whitley RJ, Gnann JW Jr. Herpes zoster in the age of focused immunosuppressive therapy. JAMA. 2009 Feb 18;301(7):774-5.

Wilson JF. Herpes zoster. Ann Intern Med. 2011 Mar 1;154(5):ITC31-15.

Yawn BP, Wollan PC, Kurland MJ, St Sauver JL, Saddier P. Herpes zoster recurrences more frequent than previously reported. Mayo Clin Proc. 2011 Feb;86(2):88-93. Epub 2011 Jan 10.

|

Review Date:

5/31/2012 Reviewed By: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M., Inc. |